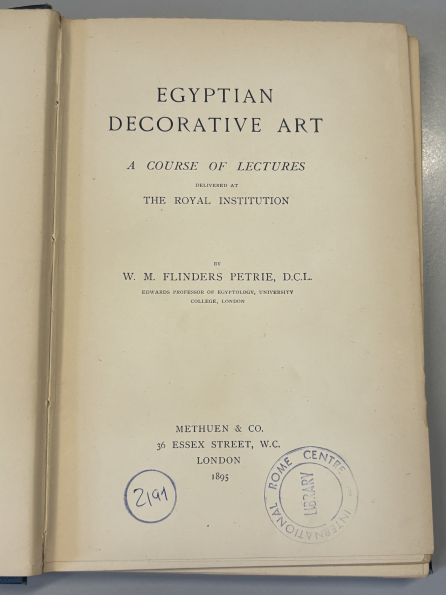

Relatively small, but not because of this less important, the volume Egyptian Decorative Art: A Course of Lectures, published in 1895 is one of the many precious representatives of the Rare Book Section of ICCROM's Library.

Bounded in a dark green cover and containing 128 yellowish pages with a magic smell of last year’s autumn leaves, this cycle of lectures studies the evolution of various motives and decorative elements in Ancient Egypt.

The author – Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie, who was a professor of Egyptology at University College London – observes how design was strongly decorative, pointing out the love of form and of drawing amongst the Ancient Egyptians.

For four or five thousand years, Egyptians maintained the use of pictures (contained in the initial pictorial writing) rather than adopting easier abbreviations, as the Chinese or early Babylonians did. The artistic form, though modified through centuries, remained constant.

Flinders Petrie goes through the main elements of decoration, classifying them in four divisions, starting with geometrical forms as the first ornaments of importance in Egypt.

The zigzag line, one of the simplest and the earliest kinds of ornament, occurs on the oldest tombs, at about 4000 BCE. From the earliest times it was symmetrically doubled.

The spiral, or scroll, whose origin is attributed to a development of the lotus pattern, is said to represent the wandering of the soul, and is considered one of the greatest elements of Egyptian decoration.

The natural forms of feathers and flowers, plants and animals, were not generally imitated until a later time. The feather pattern, for example, is used frequently on the sides of thrones, from the XVIIIth dynasty (16th and the 13th centuries BCE) to the latest times.

The use of flowers for ornament may seem quite obvious, but only a few were adopted for decoration. The lotus was so widely spread that some have seen it as the source of all ornament. After that, the most common were the papyrus, the daisy, and the convolvulus, together with the vine and palm. Wood and stones were also imitated by painting, and red granite was frequently copied on the recessed doorways of tombs.

As for animals, the ibex was the favourite in decoration, though not introduced until the XVIIIth dynasty. Birds were also quite a common subject.

Turning to the men shown in decoration, in the Period of Empire (between the 16th and the 11th centuries BCE) the figures of captives were introduced to emphasize the power of the king. These first appear in the great change which overcame Egyptian art following the Asiatic conquests.

Certain forms of ornament were a direct result of the structural necessities of buildings or objects. Wooden framing was one of the early motives.

Continually imitated in the stone figures of doorways in the tombs, it shows that a frame or grate of joinery must have been used for the porch of large houses. This design allowed light and air to enter while keeping the door fastened, demonstrating its suitability for the climate.

The true value of structural ornament lies in its retention as decoration long after losing its original structural purpose. This preservation points to a bygone era and conditions that have since disappeared.

Finally, many constantly repeated ornaments in Egyptian work had a symbolical intention.

The uraeus snake or cobra in his wrath became an emblem of the king thanks to the dignity and power of the animal.

The symbol of the globe and wings, which dates to the beginning of the monumental age, may have expressed the same idea of power, of life and death, of preservation and destruction.

While the scarab, though very common as an amulet, is not often seen in symbolic or decorative use otherwise.

At the same time, the author warns us not to “see a hidden sense in every flower” (a “fanciful habit of Europe” as he calls it), as for example the lotus ornament was merely a thing of beauty rather than a sacred plant.

Written in simple language, the volume represents a precious source not only for Egyptologists, but also for those who would love to get acquainted with the decorative motifs of Ancient Egypt.

The work demonstrates how the decorations were a reflection of the Egyptians’ day to day life in its most practical aspects, but also of the way they perceived the universe and of the symbolic meaning they conferred it.

ICCROM’s interest towards the conservation of Egyptian Art has been expressed in bringing together a collection of published materials and relative documentation such as these beautiful lectures. In addition, ICCROM activities for the conservation of Egyptian monuments carried out since the 1960s have generated rich and valuable archival collections composed of correspondence, mission reports, photographs, audiovisual material, as well as samples. The Mora Samples Collection holds over 75 samples from more than 15 Egyptian monuments, including the Nefertari Tomb, Tutankhamun Tomb and Abu Simbel Temples.