At the turn of the 15th century, Pietro Bembo, a cardinal, a humanist, and a writer, set an example for those who wished to experience the garden as a place of refuge and meditation. Even today, the garden remains capable of providing moments of tranquility and a break from our hectic lives—a place of pleasure par excellence.

Not only. A garden is also a place where observing the seasons changing makes us conscious of the passage of time in our lives. The water in the fountains, stagnant or gushing, reflects our very soul, which can be clear and calm or sometimes rippling on the surface and turbulent in the depths.

That may be why gardens (often linked to our childhood home) become places to which we remain strongly attached throughout our lives, even when we change countries or cities or leave our old friends behind.

Yet, the space reserved for the garden in the sphere of cultural heritage protection remained limited for a long time. In fact, even today, the VIII G book section, dedicated to the conservation of gardens, is not one of the largest in the ICCROM Library.

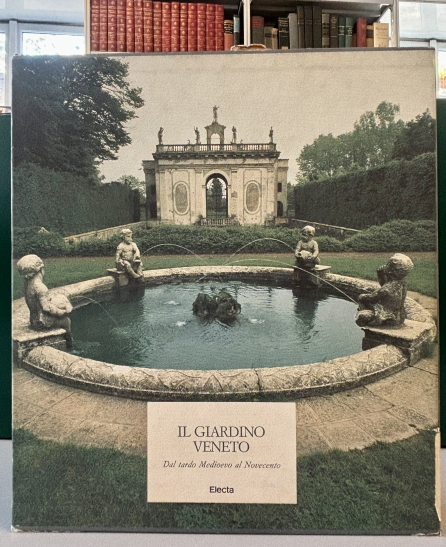

Seeking to fill this gap, our Library proudly houses the beautiful volume, "The Veneto Garden: From the Late Middle Ages to the 20th Century", edited by Margherita Azzi Visentini and published in 1988, which explores the transformation of meaning and functions of the garden in Veneto over the centuries.

From the Middle Ages to the 20th century, the garden went from simply an outdoor extension of an architectural construction to becoming a villa's true protagonist (as is the case of the Villa Barbarigo at Valsanzibio).

It goes without saying that these transformations occurred along with changes in artistic trends.

In the Middle Ages, gardens were linked to monasteries and castles and characterized by predominantly practical and symbolic functions, such as cultivating medicinal herbs or using them for meditation and spiritual rest.

Later on, this latter function persisted, acquiring a further intellectual characteristic. At the end of the 15th century, the Benedictines of San Giorgio Maggiore showed pilgrims the library and the garden as the two most favourable wonders for the spirit in their convent. In contrast, the garden represented the most proper area for reading.

During the Renaissance, gardens started to be characterized by symmetry, geometry, and architectural elements such as fountains and statues.

At the same time, notes of Francesco Sansovino show that in the early 16th century, about a hundred palaces boasted gardens of their own. Amid those is Palazzo Contarini dal Zaffo on the Grand Canal in Venice, which still retains the rare image of an early 16th-century Venetian Garden.

With the Baroque entering the scene, an emphasis started to be put on opulence, theatricality, and interaction with the surrounding landscape. This included water special effects, illusory perspectives, and complex designs of hedges and flower beds.

A curious example is the project of Prato Della Valle in Padua, designed by Andrea Memmo (an extraordinary superintendent of Padua between 1775 and 1776). Memmo implemented an authentic project of a square in the form of an elliptical garden, which looked like a theatre.

The proposal was oriented toward constructing a theatre against the explicit prohibition established by a 1763 law that prevented the construction of new theatre spaces, in addition to existing ones, in cities outside the capital. Setting aside this initial false objective, Memmo has brought to life land reclamation works, reorganizing a vast swampy and uncertain area of the city, incorporating in this way functions of spectacle, fairs, and public promenades.

In the Age of Enlightenment, Veneto gardens began to be characterized by a significant focus on nature and science, particularly exotic plant collections.

The 19th century saw a gradual transition towards more natural and landscaped gardens inspired by the principles of Romanticism. A transition ended in the 20th century with the introduction of modern styles and international influences.

The garden, whether an integral part of a villa or a self-sufficient creation, is still perceived in the context of its surroundings and comprises many components: botanical and architectural, figurative and aesthetic, literary and poetic.

And that is when the image of Bembo is recalled—a poet who thought of admiring the garden from the loggias and windows opened wide onto the meadows and waters flowing from rocks and fountains that belonged to literature rather than to life.

From this perspective, the garden in Veneto was seen as a non-place, suspended in eternity, dispersed in time and space.

Here, the gaze of memory becomes the determinant, as it makes us realize that preserving the garden also means preserving the memory.